tony evans, swansea rubber-band ball creator whose 2,600lb beauty created a massive crator in the Mojave Desert when it was thrown out of an aeroplane for Ripley's Believe It Not to see if it would bounce.

tony evans, swansea rubber-band ball creator whose 2,600lb beauty created a massive crator in the Mojave Desert when it was thrown out of an aeroplane for Ripley's Believe It Not to see if it would bounce.

Eleanor sat at her coffee table and turned on her television. She edged the volume up, notch by notch, to quash the incessant whistling that drifted in with the sunlight through the open window of her husband in the shed. Sunlight picked up dust whirlpools that swam in the air like bees, and lighting a cigarette, she amused herself with the ribbons of blue, curling smoke that pirouetted between her lips. Edward was in his element, lightly tapping away at his old fashioned typewriter and smiling at the bell when he reached the end of each line. Every so often, he risked a glance over his shoulder, to check that she was still there, waiting for his return, before inwardly beaming, newly inspired. Edward had been creating Brownie now for eleven months. She sat proudly, a beige, over-inflated lump in the middle of the shed. It made Eleanor want to vomit every time she caught its synthetic taste in her throat.

Eleanor sighed a heavy gulp of resignation as she heard the ominous thump of thick envelopes on the welcome mat. The bands, or, the sponsors, as Edward affectionately referred to them, had been arriving steadily since his appearance on the local radio breakfast show. Callers had chirped across the airwaves, offering sympathy for Edward’s predicament, applauding him for his drive and vision. Queues of people, all sitting in their condensation coated cars, willing the day to be over, listening to the fairy story of the man with no job, but a dream - with the promise of television appearances.

So notorious was Edward and his curious obsession that donations had begun to arrive in envelopes with little more than Mr E. Robinson, Norfolk scrawled upon them. Thick, padded, brown paper envelopes. Small, colourful, sparkly envelopes for thank-you letters and party invitations. Envelopes containing post-it notes of encouragement or neatly hand-written letters of admiration. Initially the parcels had arrived silently, although not surreptitiously, with little more than a grin to salute their presence. But as the ball got bigger, so did Edward’s regional reputation, and with that, so did the fan club. Frequently now the doorbell rang and Geoffrey, a young, ruddy faced postman, greeted Eleanor’s husband with a hi-five and a stack of letters, tied together with a coloured rubber band. Even the tinkle of the doorbell made Eleanor seethe with rage.

She walked into the hallway, her heels click click scraping across the laminate flooring, and bent down with a sigh to pick up the post. She rifled briskly through the stack of letters and retrieved the gas bill and an anonymous looking white envelope addressed to her. Smiling slightly as she observed the pile was smaller than yesterday’s, she clicked out into the garden and placed Edward’s post through the rusty red cat flap on the shed door.

‘L!’ came a muffled cry.

Eleanor crept inside, holding her breath at the tacky smell.

‘L, how does this sound?’ He cleared his throat.

Edward’s voice deepened into his reading voice, his media voice, a new voice he had adopted when telling the story to local journalists and young children.

It begins rather innocently. After seventeen years loyal and punctual service at XTC Energy, Edward had been presented with a modest cheque and a chunky but disappointing nine-carat gold-plated watch. Following four months of temping, the disillusioned Edward Robinson began working at the computer support department of Baden & Baden. Low level, low pay, low libido, low volume; at thirty three he felt sixty-three, not least because he’d already survived his first redundancy.

And then, he met Stephen Perry.

Eleanor knew this was her cue to chuckle at the insider’s reference to the great inventor of the rubber band. She smiled wanly, careful not to let the bile seep through her dimples. Edward continued.

There he had been, just idly sitting in a sterile little cubicle, following the spiral motion of the screensaver and toying with a rubber band. Thick and fat, Edward wrapped and unwrapped it compulsively around his index fingers before subconsciously -as if, Edward added, guided by some supernatural force - taking a thinner band and wrapping it tightly around the first. Now on the threshold of a powerful and primitive rhythm, Edward snatched another into his hand and swept it around the two linked, elastic friends, before twirling another into the bouquet, and yet another, all the time staring into the vortex of the monitor.

Leaving the office with a record-bag full of stolen rubber bands and a small but satisfyingly solid and round beige ball in his pocket, Edward felt somehow at peace. That evening had been spent with Eleanor, drinking wine and laughing at each other, while Edward added to the ball, looping his fingers around band after band, fingers tingling slightly and palms sweating as the bands slipped around each other with a twang and a ping and all the while it had felt like music.

As Edward’s story continued, Eleanor’s eyes glazed over.

Clicking back to her coffee table, she eased the letter out and began to read. Her heart flipped up onto her tongue as she recognised the large, flat, irregular writing.

Eleanor

You may be wondering why this has come now, and I’m sorry that it never came sooner. Truth be told, everything I told you was a lie and I had no intention of ever contacting you. I forgot all about you, not completely, not all, that’s another lie, but almost.

I opened the newspaper last week and saw you with your husband. I remember him, rolling around after you. Bad teeth. I was surprised. Still, I gather he’s quite the local celebrity these days, so I hoped that if I wrote, it would reach you soon enough, now that everybody appears to know you. Anyway, I live in Brighton now and you should know I own a business, a wife and three children. Always have.

I suppose what I’m trying to say is, would you like to meet again. I just want to see you and explain myself, if you feel you want an explanation. I appreciate that you might not, or even, that you might, but would rather not see me again.

I would come to you. I feel that would be easier, and more courteous in light of all of this.

Forgive me

Lars

Eleanor cast her eye to the shed. There was no sign of Edward, although the ball appeared to be rocking slowly. A mobile telephone number beckoned below the signature. Eleanor paced across her living room before clicking out the front door and down to the glass phone booth outside the pharmacy. Her hands quivered so much, she could barely press the keys.

‘Hello’.

Eleanor remained silent.

‘Hello’.

The voice sounded different somehow.

‘Hello?’

and then ‘Who is this?’, this time slightly irritated.

Then, ‘Eleanor?’

Alarmed, she slammed the receiver down.

The letter from Lars stayed in a long forgotten drawer stacked with postcards and blurry photographs. Eleanor continued about her daily business.

Edward gave an interview to a men’s magazine, slotted between a spread of seductive pouts and a retrospective of Stanley Kubrick’s films. A photograph of Edward, arms around the ball, rested between text detailing the technicalities of rubber-band-ball construction, framed with the caption;

‘I love Brownie, she’s become my life. It seems like the most natural thing in the world –

beautiful things in nature tend to be round’.

Beneath this was a series of photographs, for the enthusiast, of the biggest ball in history and its 400mph descent from an aeroplane – not Edward’s. Crackling sparks had created a filigree halo around the dust swept up by the collision of the 2524lb mass of the ball with the sands of the Mojave Desert. Finally, there was the crater left in the earth, surrounded by broken strands of rubber bands, camera crews and reporters.

Like Eleanor’s letter, this magazine had been relegated to a disused drawer - for Edward, a reminder of his irreconcilable failure.

The ball reaches a point where your ordinary common or garden bands begin to break, unable to reach around the circumference. With relatively little difficulty, Edward had succeeded past this minor hurdle, the 30lb crunch point, at which many enthusiasts are forced to fall. With assistance from his ex-boss in exchange for a plug on local radio, Edward kept himself in rubber bands. But no sponsers would commit themselves. Edward could find no one who had faith in his dream to smash the world record, many companies believing it impossible or unprofitable.

He began to realise, to Eleanor’s silent delight, that he was little more than a curio, an oddity to fill the space in the local news when there was a drought on violent crime and celebrity scandal.

For a brief and blinkered period, Edward had comforted himself by building accompanying balls for Brownie with the remaining donations. Soon, the shed floor was blanketed in a precarious sea of balls, the larger orbiting the now defunct Brownie, who presided over her entourage of lesser companions. August turned to September turned to October. Gradually the smaller balls disappeared, given away as gifts to neighbourhood children or prizes in community raffles, until Brownie was left standing isolated in the shed, insulated by a thin coating of dust.

Defeated, Edward sheepishly attempted to inch his way back into the house.

Initially, Eleanor appeared reluctant. A series of inevitable rows followed…

But gradually, as the nights stretched out and mornings arrived with a heavy frost. moss began to hug the shed walls and rust sealed the door shut. Eleanor found herself in a photograph, placing the angel on their Christmas tree, at the end of a ream of now redundant images of Brownie. To her knowledge, Edward discarded all but that last picture he had taken to finish the film. In fact, it seemed so long since he had taken those photographs, he had forgotten what they had been of.

One Sunday morning, in an upmarket restaurant where the happy couple sat eating brunch, the proprietor enquired how Brownie was doing.

‘She’s doing fine, I think,’ replied Edward. ‘We don’t see each other anymore’.

So, it came as something of a shock when a still-hung-over and post-coital Eleanor accidentally opened a letter addressed to her husband. It read:

Dear Mr Robinson

We have been following your progress with ‘Brownie’ your rubber band ball, and understand that you have since abandoned your project due to a lack of corporate interest. We feel that this is a great national loss, and consequently, we are delighted to be writing to you with the offer of an eighteen month contract with Persuasion Suppliers Ltd., enclosed for your perusal.

Persuasion Ltd., amongst other things, is the major wholesaler of rubber products in the UK and Europe. Based in Brighton, we specialise in industrial rubber bands. We would be honoured to assist you in your endeavours by producing customised bands for your exclusive use in the creation and completion of Brownie. All we ask for in return for our support is that you allow Brownie to become our registered trademark, and following her completion, that you permit Persuasion to use Brownie in our subsequent promotional campaigns, for which you will be paid a substantial amount (see contract).

We sincerely hope that you will agree to our offer, and we greatly look forward to hearing from you in the near future.

With best wishes

Persuasion Ltd.

The signature below was unmistakeable.

Without a word, Eleanor walked to the kitchen and spreading the letter flat on her coffee table, took a pen and wrote in bright red ink diagonally across the document:

Lars - Not now. Not ever. Else I’ll tell your wife.

E.

Replacing the letter in its envelope and resealing it, she affixed a new stamp and triumphantly wrote Return to sender across the top, before slipping it into her handbag. Then, without giving it another thought, she put the kettle on and set about making breakfast.

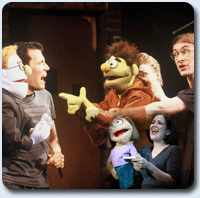

to commemorate the eye-opening wonder that is minifig's and mine 8 year anniversary, i did what any self-respecting girlfriend would do and dragged her boyfriend to a musical, and he loved it.

to commemorate the eye-opening wonder that is minifig's and mine 8 year anniversary, i did what any self-respecting girlfriend would do and dragged her boyfriend to a musical, and he loved it.