he do the police in different voices

In his 1960 essay on Image and Experience, Graham Hough argues against the presence of a single consciousness in The Waste Land, asserting that for a poem to exist as a unity, we need the sense of one voice speaking. Assessing the collation of images in the poem as the negation of method, Hough’s evaluation of one of the great 1922 literary mysteries finds its echo, and enemy, in Martin Rowson’s smartarse but relentlessly funny comic strip The Waste Land. By reinventing Eliot’s poem as a giant murder mystery investigated by his narrator Marlowe, a composite of Raymond Chandler’s toughest detectives, Rowson is able to give the impression of a single consciousness in his retelling, whilst admitting the presence of the multiple ghosts that haunt The Waste Land.

The diverse voices within Eliot’s Waste Land function like a greek chorus, echoing the poem’s themes of social, sexual and communicative collapse and creating a platform for the prophetic voice of the absent, unnamed protagonist. Eliot’s use of literary quotation, allusion, free, indirect and direct speech facilitates the compression and simultaneity necessary for the communication of the depersonalised but universal experience of The Waste Land. By re-shaping Eliot’s nameless, rootless teller in the poem into that of a frustrated detective, (the role more often assumed by the baffled reader) Rowson physically presents the disembodied voices of the poem as a cast of grotesquely familiar characters in a weird comic-strip. It quite literally turns the poem inside out (and it looks pretty good too)

As with Eliot’s poem, Rowson’s comic starts with a corpse, only Rowson gives the reader DIC Marlowe to guide them through the poem’s allusions, acting as a hard-boiled trench-coated replacement for Eliot’s Tiresias, casting Eliot-biographer and all-round-London-expert Peter Ackroyd as his cab-driver. Similarly, Rowson’s Game of Chess starts with Marlowe revisiting an old flame. Remembering the first time they met, he drawls ‘She’d looked like a million dollars, and I’d felt like a bent dime. Then again, looks ain’t everything…she still had a mind like a marshmallow.’ His ex is, of course, that neurotic crazy lady from Eliot’s poem with her nutso neurasthenic fixation on the ‘wind under the door’.

Eliot’s original ventriloquist pub scene from A Game of Chess contains no fewer than fifteen repetitions of ‘I said’ as his gossipy speaker retells a conversation she had with ‘Lil’. Touching on many of the poem’s themes in its allusions to infidelity, abortion, death by childbirth, decay and war, the dialogue in the pub is delivered almost entirely in reported speech, removing the sense of Lil’s own voice in the conversation, implicitly linking sexual sterility with the loss of speech. By beginning with modernism's version of Eastenders and ending with Shakespeare’s Ophelia, no word spoken in the pub scene belongs to the speaker. Thus, it makes odd sense that when Marlowe steps into the same boozer, he sits and drinks with Rowson’s Where’s Wally-type composite of modernist movers and shakers, including William Carlos Williams, W.B. Yeats, Henri Gaudier Brezska, Wyndham Lewis and T.S. Eliot. These comic book faces are just a handful of the many conflicting spectres that hover over any consideration of Eliot's poem, whilst also being just some of the literary and visual puppeteers choreographing Rowson's structure.

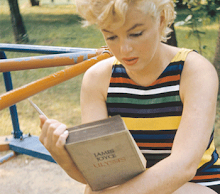

Eliot's collapsing towers and resurfacing corpses reappear in Rowson’s noir-thriller as drowned bodies and strip clubs. Seurat's Parisian picnic turns into a Thames-sewer nightmare (see above) Eliot’s physically and psychologically fragmented Thames-daughters reappear as Rowson's sullen whores on a break from their twice-nightly floor show as The Water Babes. They are played by Dorothy Comingore, Lauren Bacall and Marlene Dietrich. Where Eliot spreads the body parts of his Thames daughters across London, surfacing in Richmond, Kew and Moorgate, Rowson’s Dietrich draws on a cigarette and hisses through the smoke ‘Nah ‘e’s ended us up in Margate. On the beach we done it. Id’ve rather ‘ad a manicure.’

In Tradition and the Individual Talent, Eliot stresses the importance of a poet’s own sense of history, asserting that it is this that will compel one to write ‘with a feeling that the whole of the literature of Europe from Homer and within it the whole of the literature of his own country has a simultaneous existence and composes a simultaneous order’. By choosing not to elevate Shakespeare with quotation marks in the Game of Chess, Eliot strives for this ‘simultaneous existence’ and ‘simultaneous order’ that he felt was necessary for good poetry in which a writer is ‘most acutely conscious of his place in time, of his contemporaneity’. By translating this idea into a series of comic book panels and populating his work with pop-culture and high-art phantoms, cinematic and literary corpses, burnt-out critics and blockbuster sellers, Rowson continues Eliot’s line of thought. However, unlike Eliot's expectations on his intellectual superstar of a perfect reader, Rowson doesn't even expect Marlowe, his own creation, to solve the poem's crimes.

As Marlowe comes to the end of his investigation followed by Eliot’s Buddhist chants, pictured as a tambourine-slapping bunch of Hari-Krishnas, he is left with no recourse but to interrogate Pound and Eliot themselves. They are no help at all, wittering in Latin about vegetation myths against backdrops of vorticist masterpieces. It would apoear they also have a pretty half-arsed idea of what they're trying to achieve. Marlowe’s response? “Vegetation myths? The only vegetation myth I ever heard was that you can sit on your ass behind a desk in the D.A.’s office for twenty years and call it work…”

Consequently it should come as no surprise that instead of Eliot’s unifying ‘Shantih, shantih, shantih’ (the peace that passeth all understanding) that closes his poem and goes some way to piecing together ‘these fragments I have shored against my ruins’, Rowson gives us Warner Bros’ budgie-baiting Slyvester the cat lisping ‘Thantih, Thantih, Thantih, Thuckers’.

It made me laugh. Lots. Even though I think I understand this even less than I do The Waste Land.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home