sort of fun, don't you think?

Some people say what I do isn't very feminist. I say it's pretty liberating to get $20,000 for 10 minutes...most women want to be sex symbols, even if they don't admit it. Imagine being considered not for your mind but for how you look. Sort of fun, don't you think?

Some people say what I do isn't very feminist. I say it's pretty liberating to get $20,000 for 10 minutes...most women want to be sex symbols, even if they don't admit it. Imagine being considered not for your mind but for how you look. Sort of fun, don't you think?

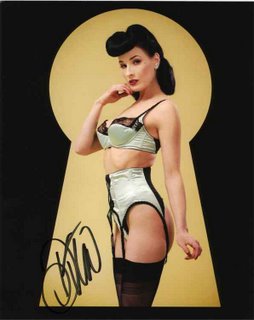

the ravishing Ms Dita Von Teese

It's an interesting point, and one you're almost not allowed to make these days, for fear of being misunderstood. But, speaking for myself, yes, I think it would be sort of fun. It is sort of fun.

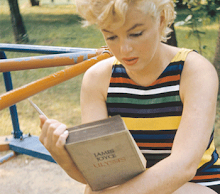

I decided quite early on as girl that I did not want to be a girly girl - although, I think to a certain extent, it's a choice that's made for you. You're either one of the prettiest girls in your class, or you're one of the sportiest, or you're one of the nicest, or you're one of the bolshiest, or you're one of the smartest. I was smart (and devilishly competitive) and instinctively solitary. I was never the girl the boys boasted about. I worried that if I was, that would be all I could be.

As a teenager I dressed like a boy - my hair was extremely short and i'm not, nor ever will be what you'd call volupturous. But in my own self-styled way, I felt pretty – and pretty good, because i was most definitely not a boy. i like nothing more than to feel feminine, and nothing makes me feel more like me than denying that impulse. i still think i look best in drag, actually - more in a shirt and tie sort of way - on a dressy day, maybe a trilby. but maybe that's because i can't think of anyone more beautiful than diane keaton in annie hall. but that's a different post altogether.

being a sex symbol is different from being a sex object. Being a sex object is about passivity, stillness, boredom. It’s the closed eyes, the open mouth, the spread legs, the same old pose repeated endlessly with a different woman pulling the same goggle-eyed grin and saying nothing more than "I’m available – do with me what you will".

But a sex symbol – now she is a promise, an idea, a thought. She’s the restriction of her corset, the slovenly pyjamas that belong to somebody else, the tautness of her calf muscle in the stiletto heel, no-bra confidence and couldn’t care less bitten nails. It’s the two hours it takes of an evening to iron your hair and the two hours it takes to make it curl. it's both what you are and what you could be, and most importantly, what you want to be.

as that crazy lady elizabeth wurtzel says about the archetypal "bad girl", "it's a woman who understands that she will achieve her apotheosis when anybody can project any idea, any neurotic impulse or erotic fantasy, onto her person, because she is either the parallax view, the human Rashomon - because she is either that beguiling or that empty".

but, unlike ms wurtzel, i think it's the either/or that's important.

for the album cover of "strange little girls", a beautifully bleak album of cover versions, tori amos appears in no less than 13 different guises. you can buy the album with any one of the thirteen toris, but once it’s yours, you get all the delight of the other twelve inside. She is every single one of those strange little girls, and none of them, and each disguise delivers a separate, considered and gorgeously exaggerated symbol of some tiny little piece of who she is.

being a sex symbol is my being whatever you want me to be, but strictly on my terms.

Imagine being considered not for your mind but for how you look – sort of fun, don’t you think?

little bo peep & the geisha girl

apologies for the appalling absence - have moved house and no longer have a dial-up connection, which means using blogger is much less annoying. will be back soon. here's a very old story (5 years almost to the day, so be gentle with it - it hasn't aged well, but it's old enough that i'm no longer precious about it) to fill the gap while i tidy up my other writing in preparation to upload it next week - gosh, you lucky lucky

lucky people...

little bo peep & the geisha girl (a love story) Her bedroom window is opposite the study. For the past two months she has been sleeping better. I hadn’t slept since the first time. At first it just pulsated behind the walls, a sly, persistent hum like the sound of the extractor fan in that cheap hotel in Ankara. Then it slid under the door, seeping into my ear and weeping out of my eyes like a cut that’s gone septic. It clogged up the house with its putrid decay until the walls were coated in an insulating silence.

A disconcerting quiet settled on the rooftops when Rebecca went to sleep. It throbbed around the house. It was so loud it kept me up each night. All I could do was lie awake in bed, staring into the dark and play music in my head. It went on for weeks; hearing nothing but the occasional drone of a passing car or the screams of a Friday night fight. Into the night I’d lightly tap tap tap against the keys of the computer, producing mediocre notes whilst absent-mindedly browsing the Internet for car accident victims and teenage pornography. Every night it became harder and harder to fall asleep, the minutes clicking by faster and faster until I couldn’t sleep at all. I’d set myself targets each night - learn how to juggle, roll one hundred cigarettes, a poet for each letter of the alphabet. The nights were long coach journeys to places you couldn’t be bothered to visit. They were a tour of the National Gallery when you were five. Josh’s presence had become my absence. I knew he couldn’t be mine.

I’d known of her since she’d moved. She was a fragile, pale bird with dark hair and pin legs. She had a sullen face and eyes, round and glassy and dark eyes. I hadn’t spoken to her, but I’d sometimes see her on her way to work in the mornings. Occasionally she would nod a steely acknowledgement. I wasn’t spying, but I caught a glimpse of her one night. It was late, must have been three-ish, and I noticed her light was on. Except it wasn’t a light, but a glossy purple lava lamp bouncing biomorphic shapes against the walls so that she looked like a singer in a cheap music video. A red glare shimmered in a corner and, shoving my glasses on, I could make out that it was one of those portable heaters. A white heart-shaped sheepskin rug lay on the floor and a Japanese Lantern cast cut out geisha faces across the room. What with the heater and the lava lamp and the faces the room was fused with a scarlet-violet light that was part club, part massage parlour. I leant up against the window and watched. She walked over to a dressing table iced with coloured bottles with intricate tops and laced with lingerie in lurid colours. She picked up a decapitated doll wearing a glittery tutu, taking from its chest cavity a packet of Rizla and a small plastic bag, like the ones in the labs at school. She rolled a spliff and smoked it. Then she lay down and went to sleep with the lights on. Envious, I watched.

The following night at about eleven I sat at my desk marking essays on ‘Of Mice and Men’. I could hear Josh crying downstairs, high, long whines that reverberated over Rebecca’s coos and sighs. I opened the window and peered out across the street, absent-mindedly looking into the dark of next door’s bedroom window. Lighting a cigarette I prostrated myself across the window-sill in a desperate attempt to blow the smoke outside, but the wind was blowing in the wrong direction and it breezed back and clung to my T-shirt. I could make out her thin silhouette in the dark, sitting, her back towards me, head in hands at the dressing table. The walls were a midnight grey, slices of light penetrating the room at abrasive angles. Her narrow shoulders were shaking and it looked like she might be crying. I started and moved away from the window, suddenly embarrassed. When I looked again she was lying back on the bed, smoking. From that day, Curly’s wife took on the look of the girl next door.

The next night, at about eleven, I saw her. Back towards me, seated and gazing into the mirror like the lovechild of Snow White and her wicked stepmother, she sat and cried night after night while I watched. The longer I watched the less we slept. And, as the fortnight stretched into a month, and a month into a term and a term into six months, I came to know her ritual of tears before bedtime, coffee and smoking.

Some nights we’d read together, or maybe I’d read to her, something I’d written when writing was living not working. And sometimes it would help her get to sleep and sometimes it wouldn’t. We would sit and roll and smoke together. On the nights that she turned her back on me and cried I did the same, until I could barely see anything at all. She became the only person I could talk to amidst the sea of wet wipes, fluffy bunnies and liquid food. On the rare and beautiful nights that we slept together, I took her and held her and stopped hearing the cries from downstairs. I didn’t care anymore if the baby in the bulrushes was found or not. I just wanted to disappear into that place when I slept where I had a barge and an old fashioned typewriter. The bed was cold now. There was no longer anything in it for me.

The mobile that hung in the nursery would turn and turn and turn to its tinkling music of nursery rhymes, casting Little Boy Blue across the walls like her geisha faces. The sounds of baby breathing and baby coughing and xylophone mobiles danced through the little speaker into my office. Every movement, every stirring in his dreams was piped into my night. One night, when the rustles turned into screams and bleats of hunger I took the plastic monster and threw it out of the window into the space between us and watched it break onto the gravel, shattering a Bo-Peep. Yet still the noise continued and the whirring of the mobile went on as little pastel demons marched across the nursery.

We passed each other in our parallel gardens. She’d march out of the front door, bare feet in T-bar shoes like my sister’s doll with the pull-cord that broke when I kicked it, only with impossible heels. Wet hair wrapped in a gypsy scarf and rucksack that clattered with badges and buttons, she’d chain-smoke her way to the bus-stop, ignoring my punctual shirt and shoe polish. The day was not for us. One afternoon in the half-term I went shopping for a cheap and forgotten anniversary card and a perfume that I barely remembered the smell or the name of. She was in the coffee-house, small notebook and day-glo pen in hand, intermittently delivering cake. She did not acknowledge me.

I called her Deborah. I whispered it into the air when her shoulders shook in the dark. I felt her gratitude on the nights she washed her hair or painted her toenails for me. If we got an early night I would watch her mask slip off as she wiped away her face onto pads of cotton, revealing pinky cheeks and open pores. Her eyes and her lips slid off her face. She became only shape and shadow and visited only me. My eyes became darker and my back, bent out of shape and hunched. The piercing florescence of the strip lighting in the halls shot through the memory of the walk down that hospital corridor sixteen months earlier. I shuffled from class to class, sighing reprimands and murmuring assignments. I came to loathe the serpent-green night-gown that hung on the back of the bedroom door. I could not see my eyes in theirs. All was whispers, rustles and the whirring of a nursery rhyme.

Then one night she fell asleep and stayed asleep. I sat on my watch for seven hours, looking in her window through the darkness, equipped with a pair of binoculars I’d once used when Rebecca and I used to go to gigs, together. I watched her chest rhythmically rise and fall. She barely stirred. I remained angry and jealous with her for weeks afterwards. I maintained my close watch on her, just in case, but like clockwork every night at eleven she drifted off to sleep. The leaves fell off the trees and she went out and bought some curtains.

And then, last night, one eye on lesson plans, the other at the window, I heard the door go and the tinkling stop. I felt the din of the silence sink into the floorboards. The walls sighed with relief and the floorboards creaked and loosened. The duvet on my bed rose up to welcome me and the pillows pouted seductively. I woke up in my clothes, drooling. Rebecca had gone to her mother’s and the only place to go now, was to sleep.

Some people say what I do isn't very feminist. I say it's pretty liberating to get $20,000 for 10 minutes...most women want to be sex symbols, even if they don't admit it. Imagine being considered not for your mind but for how you look. Sort of fun, don't you think?

Some people say what I do isn't very feminist. I say it's pretty liberating to get $20,000 for 10 minutes...most women want to be sex symbols, even if they don't admit it. Imagine being considered not for your mind but for how you look. Sort of fun, don't you think?